Lactate and lactic acid have had their fair share of controversy over the years. Many people have heard of one or both of these molecules but knowing what their functions are and why they’re important to us in endurance sports is a complicated procedure!

So, where do lactate and lactic acid come from and why are they important?

The Chemistry

Don’t worry, this won’t last long and you can skip this bit if you wish!

Lactic Acid = C3H6O3

Lactate = C3H5O3

Lactic Acid has one more hydrogen (H+) atom, giving it a “positive charge”. Lactate is what is left over after lactic acid has donated a hydrogen atom during a chemical reaction, the hydrogen ion is therefore removed from lactic acid.

Lactate is the primary molecule that exists in body fluids and is derived from glucose (blood sugar) and glycogen (stored blood sugar in the muscles). Because we know that glucose and glycogen are used in anaerobic metabolism we can conclude that the higher the exercise intensity, the more lactate you will have in your muscles and blood.

How much lactate is in my body and what do I do with it?

Although I mentioned that more lactate accumulates as we exercise at a higher intensity, we do still have a level of lactate in our bodies when at rest. Lactate is present as part of normal metabolism and most of it is actually used for fuel (maybe not what you were expecting to hear?) For example, as well as other tissues, the heart is a big user of lactate as a fuel.

As well as being a fuel, lactate can be converted back to glucose in the liver and back to glycogen in the muscles. It’s quite a versatile molecule wouldn’t you agree?

Lactate can go up to levels in muscles 20 times the level when at rest!

Does lactate produce “The Burn” when I exercise hard?

Well, it’s not actually fully understood. It’s possible that the burning sensation you experience when you are working more anaerobically (and therefore producing more lactate) is caused by “acidosis” (an increase in acidity). It’s unlikely that the burning is caused directly from a rise in lactate. Acidosis results from the overproduction of acid within the body and is an extremely complicated process that involves multiple systems of the body. So if you hear someone say “X is what causes the burn” then you can be sure that it’s just opinion and not based on much science. We simply don’t know for sure what causes that burning sensation, that’s not to say it doesn’t exist though!

Does lactate cause the soreness in days following hard exercise?

Have you ever been recommended to get a sports massage or do some light exercise the day following a race in order the “flush” the lactic acid from your body? Well, although this sounds simple in principle, lactate levels are generally back to resting levels after about an hour of finishing exercise. That’s not to say that an easy recovery session or sports massage can’t help with recovery, they just tend to be beneficial practices that assist in dealing with other bodily reactions to exercise such as inflammatory muscle damage. It’s therefore more likely that any soreness in the days following exercise is independent of lactate or lactic acid.

Does lactate cause the fatigue I get during exercise?

Up until very recently it was believed that lactate was a primary cause of fatigue when exercising. There was significant evidence that linked higher fatigue levels with higher lactate levels. However, as mentioned previously, we know that lactate levels tend to be higher with higher intensities (and therefore higher fatigue), but we don’t know whether the higher lactate levels CAUSE the fatigue. There is actually strong evidence to the contrary – some studies have shown that lactate may be a preventative factor of fatigue by counteracting the effects of depolarisation within the muscles. Like with “The Burn”, we simply don’t know for sure so anyone who states that lactate causes “burn” or “fatigue” are merely speculating. This won’t mean you’ll stop hearing BBC commentators stating lactic acid causes a 400 metre runner to start “treading water” at the end of an international race. Give the research a few more years!

Can knowing lactate levels help me train and race better?

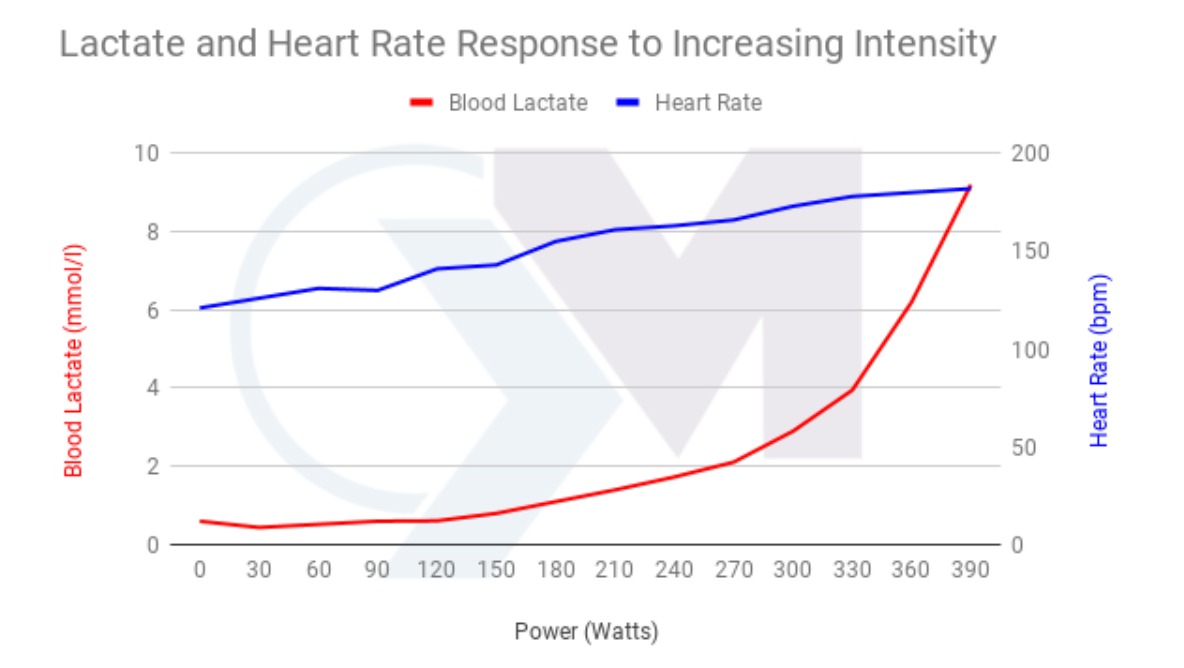

The image below shows how lactate levels corresponds with exercise intensity. Put simply, as you work more, the lactate increases. The resulting curve indicates a change in the rate of lactate production over time, work harder and the lactate will increase at a faster rate.

In science you can’t use one or two values to describe a curve, this is where testing for blood lactate becomes important. Interpreting and reporting lactate response is even more important. “Significant” points on the curve depend on what you or the tester deem important and which definitions are used. Lactate is not alone when it comes to the large number of “thresholds” available to be used for determining training zones. For more discussion on the nuances of “thresholds” relating to lactate and other markers please check out the article here.

Specifically relating to lactate, you could say that a threshold occurs when levels increase or increase “dramatically“. That could be when the level moves to “above resting”, it could be when it is two times the level when at rest, it could be four times.

4.0 mmols per litre of blood is a figure that is still often looked for in a blood lactate test despite recent evidence going against it. This point can often be described as the Onset of Blood Lactate Accumulation (OBLA). Although still frequently over-emphasised, this figure does not take into account the considerable differences between individuals and their lactate metabolism. It is therefore potentially damaging in estimating other points on the curve and/or training zones and intensities. The OBLA tries to identify a point at which lactate starts building up in the muscle because lactate transporters within the body have become saturated/reached capacity.

The Maximum Lactate Steady State

There is another point which a lot of testers try to identify – the Maximum Lactate Steady State (MLSS). This point is often used interchangeably with Functional Threshold Power (FTP) and is defined as the highest workload that can be maintained without continual lactate accumulation over time. It’s a “steady state”. Although there is no doubt that this point is useful to know, again it can’t be equated to a specific number as there is great variability between the MLSS of individuals, ranging from 2.0 to 8.0 mmols of lactate per litre of blood.

Irrespective of the “thresholds” identified, the aim of endurance training is to “shift” the entire curve to the right so that thresholds occur at a higher level of intensity. This indicates improved fitness and, hopefully, improved performance.

Don’t get carried away in the science and multiple definitions – although this is always a problem when it comes to lactate! In the next article we will outline some practical implications which can result in shifting your curve to the right, subsequently improving your endurance performance.